Plaintiffs Raymond J. Gosselin and Linda E. Gosselin (Gosselins) and Defendants Rudolph Pizzano (Pizzano), Robert M. McClane, Jr. and Gratia L. McLane (McLanes), and Garwin K. Fleming, Jr. and Page H. Fleming (Flemings) own abutting parcels that derive from common ownership and are all purportedly subject to certain putative easements and restrictions. The Gosselins brought this action under G.L. c. 185, §1(e) and (i), seeking a determination that a Site Easement and no build restriction are invalid relative to the quiet enjoyment of their property. In these cross-motions for summary judgment, the Court finds that the Site Easement remains enforceable against the Gosselins, but there are material facts at issue regarding the validity of the no build restriction that must be resolved at trial.

Procedural History

The Gosselins filed their Complaint on July 13, 2015. Pizzano filed his Answer on July 31, 2015. On February 29, 2016, the Gosselins filed Plaintiffs' Motion for Summary Judgment, Memorandum in Support of their Motion for Summary Judgment, Concise Statement of Material Facts (Pl. Facts), and Appendix (Pl. App.). On March 18, 2016, the court allowed Plaintiffs' Motion for Issuance of Ex Parte Memorandum of Lis Pendens and endorsed the Memorandum of Lis Pendens as to Defendants Robert M. McLane, Jr. and Gratia Lee McLane.

Defendant Rudolph Pizzano's Opposition to Plaintiff Gosselins' Summary Judgment Motion and Cross-Motion for Summary Judgment (Opp.), Brief Concerning the Parties Summary Judgment Motions, Response to Plaintiffs' Summary Judgment Concise Statement of Material Facts (Def. Facts), Affidavit of Rudolph Pizzano (Pizzano Aff.), and Appendix (Def. App.) were filed on April 1, 2016. On April 13, 2016, the Gosselins filed Plaintiffs' Response and Opposition to the Defendant's Cross Motion for Summary Judgment and Affidavit of Raymond J. Gosselin (Gosselin Aff.). A hearing on the motions for summary judgment was held on April 19, 2016, and the motions were taken under advisement. A Motion to Amend Complaint to add Garwin K. Fleming, Jr. and Page H. Fleming as defendants and First Amended Verified Complaint (Compl.) were filed on July 14, 2016. On August 9, 2016, the court allowed the Motion to Amend Complaint and deemed the First Amended Complaint filed. This Memorandum and Order follows.

Summary Judgment Standard

Generally, summary judgment may be entered if the "pleadings, depositions, answers to interrogatories, and responses to requests for admission . . . together with the affidavits . . . show that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and that the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law." Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c). In viewing the factual record presented as part of the motion, the court is to draw "all logically permissible inferences" from the facts in favor of the non-moving party. Willitts v. Roman Catholic Archbishop of Boston, 411 Mass. 202 , 203 (1991). "Summary judgment is appropriate when, 'viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to the nonmoving party, all material facts have been established and the moving party is entitled to a judgment as a matter of law.'" Regis College v. Town of Weston, 462 Mass. 280 , 284 (2012), quoting Augat, Inc. v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 410 Mass. 117 , 120 (1991).

Undisputed Facts

The court finds that the following facts are undisputed:

1. The Gosselins are the owners of property located at 67 Essex Street, Hamilton, Massachusetts (Gosselin Property) by a deed dated June 1, 2000, recorded with the Essex South District Registry of Deeds (registry) in Book 16375, Page 484. Pl. Facts, ¶ 1; Def. Facts, ¶ 1.

2. Pizzano is the owner of property located at 77 Essex Street, Hamilton, Massachusetts (Pizzano Property) by a deed dated April 13, 1995, recorded with the registry in Book 12986, Page 237. Pl. Facts, ¶ 2; Def. Facts, ¶ 2.

3. The McLanes were the owners of property located at 33 Essex Street, Hamilton, Massachusetts by a deed dated March 19, 1999, recorded with the registry at Book 15547, Page 437. Pl. Facts, ¶ 3; Def. Facts, ¶ 3.

4. On June 22, 2016, the McLanes conveyed the 33 Essex Street property to the Flemings by a deed recorded on July 7, 2016 with the registry at Book 35067, Page 56 (Fleming Property). Compl. ¶ 4A, Exh. B.

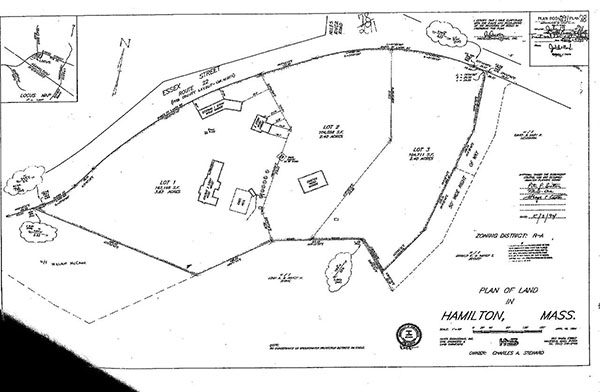

5. The Gosselin Property, Pizzano Property, and Fleming Property are shown on a certain plan entitled "Plan of Land in Hamilton, Mass." dated April 19, 1994 and recorded with the registry on July 19, 1994 at Plan Book 291, Page 78 (1994 Plan), attached here as Exhibit A. On the 1994 Plan, Lot 1 represents the Fleming Property, Lot 2 represents the Gosselin Property, and Lot 3 represents the Pizzano Property. The Gosselin Property is contiguous to both Lots 1 and 3. All of the lots abut Essex Street. The 1994 Plan does not make reference to any "No Build Area". Pl. Facts, ¶ 4; Def. Facts, ¶ 4; Pl. App., Exh. A.

6. Lots 1, 2, and 3 are largely unlevel wooded lots except for an open space or field on a ridge in the rear. Pizzano Aff. ¶ 2, Exh. A.

7. The title to all three properties is derived from a common grantor, James R. Abram (Abram), as Trustee of the Essex Street Realty Trust u/d/t dated April 15, 1994, and recorded with the registry at Book 12668, Page 568. On July 19, 1994, Charles A. Steward conveyed the three lots to Abram, as Trustee, by a deed recorded with the registry in Book 12668, Page 571. Pl. Facts, ¶ 5; Def. Facts, ¶ 5; Pl. App., Exh. B.

8. On July 19, 1994, Abram, as Trustee, conveyed Lot 1 to Scott DeF. Shiland by a deed recorded with the registry in Book 12668, Page 579 (Shiland Deed). The description of the conveyed property, which references the 1994 Plan, includes the language:

Grantor and Grantee further covenant and agree that no dwelling, structure or improvement of any kind or nature shall ever be located, constructed, placed or allowed to stand within the open space, No Build Area presently shown as a field. . . . The foregoing rights shall be deemed to run with Lots 1, 2, and 3 and be binding upon and enure to the benefit of the Grantor and Grantee, and their respective heirs, successors and assigns in and to the said Lots 1, 2 and 3.

There is no description of the "No Build Area" in the Shiland Deed or any indication as to its location or what portions of Lot 1 are within or outside of the No Build Area. Pl. Facts, ¶ 6; Def. Facts, ¶ 6; Pl. App., Exh. C.

9. On August 31, 1994, Abram, as Trustee, recorded a Site Easement with the registry in Book 12727, Page 161, which purportedly set forth a "Site Easement" for the benefit of Lots 2 and 3. The following easement and obligation were imposed on Lots 2 and 3:

1. No building, structure, fence or shrubs are to be located, installed or planted within ten (10) feet of the boundary lines of said Lots along Essex Street.

2. There shall remain a site easement for the benefits of Lots 2 and 3 for the owners of said premises to have proper visibility to said Essex Street along said Essex Street.

3. The grantor shall retain the right to go upon the premises for purposes of removing such trees and regrading as necessary to provide and allow for the ten (10) foot site easement.

Pl. Facts, ¶ 7; Def. Facts, ¶ 7; Pl. App., Exh. D.

10. In his affidavit, Pizzano attests that, based on his dealings with Abram and knowledge of the area involved, the Site Easement was intended to create safer entry and exit from Lots 1, 2, and 3 onto Essex Street, which is dangerously curvy. Pizzano Aff. ¶ 6.

11. On September 1, 1994, Abram, as Trustee, conveyed Lot 2 to Jason T. Kuplen (Kuplen) by a deed recorded with the registry at Book 12731, Page 25 (Kuplen Deed). The description of the property, which references the 1994 Plan, includes the following language, hereafter referred to as the "no build restriction":

Right and easement to use those portions of Lot 2 and 3 located within the "No Build Area" as shown on a certain sketch plan attached hereto and recorded herewith as Exhibit "A" for passive recreational uses, including, but not limited to, gardening and landscaping purposes, and for such other uses as may be mutually agreed by the present and/or future owners of Lots 1, 2, and 3 all as shown on the above referenced plan. The Grantee by the acceptance and recording of this Deed, acknowledges and agrees that the portion of Lot 2 located within said "No Build Area" shall likewise be subject to the aforesaid passive recreational uses by the present and/or future owners of Lots 1 and 3.

Grantor and Grantee further covenant and agree that no dwelling, structure or improvement of any kind or nature shall ever be located, constructed, placed or allowed to stand within the open space, No Build Area presently shown as a field. . . .

The foregoing rights and easements shall be deemed to run with Lots 1, 2, and 3 and be binding upon and enure to the benefit of the Grantor and Grantee, and their respective heirs, successors and assigns in and to the said Lots 1, 2 and 3.

Subject to and with the benefit of a site easement recorded on August 31, 1994 as Instrument No. 366, Book 12727, Page 161.

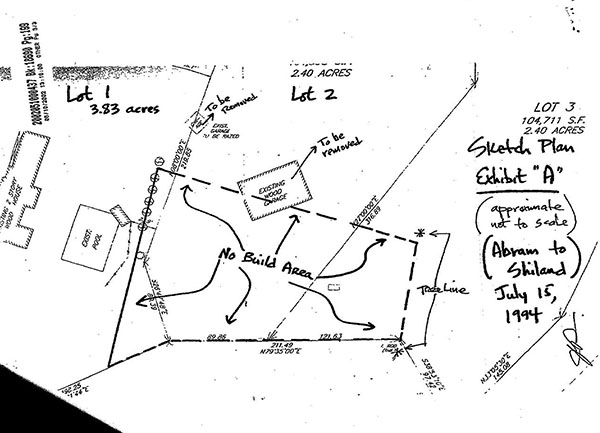

The Exhibit A sketch plan referred to was not attached to this deed, nor any other deed. It is, however, referenced in almost every subsequent deed in the chain of title for Lots 1, 2, and 3. Pl. Facts, ¶ 8; Def. Facts, ¶¶ 8, 15; Pl. App., Exh. E.

12. On December 1, 1994, Scott DeF. Shiland conveyed Lot 1 to himself and Heather M. Shiland (Shilands), as tenants by the entirety, by a deed dated November 22, 1994 recorded with the registry at Book 12843, Page 124. The deed states that Lot 1 is subject to matters set forth in the Shiland Deed, which references the No Build Area but not an Exhibit "A" or the Site Easement. [Note 1] Pl. App., Exh. H.

13. On April 14, 1995, Abram, as Trustee, conveyed Lot 3 to Pizzano by a deed recorded with the registry at Book 12986, Page 237 (the Pizzano Deed). The Pizzano Deed's description of Lot 3 contained the same language as the Kuplen Deed restricting the use of the No Build Area, referencing the Site Easement, and referencing, but not attaching the Exhibit A sketch plan to the deed. Pl. Facts, ¶ 9; Def. Facts, ¶¶ 9, 16; Pl. App., Exh. F.

14. In his affidavit, Pizzano attests that he was given a physical copy of the sketch plan in 1995 along with his purchase and sale agreement for Lot 3. He states that around 1996, Shiland brought a lawsuit against Abram and Pizzano. At the time, Abram was constructing a house on Lot 2 and finishing construction of a house on the Pizzano Property. Shiland brought a lawsuit for relief including the removal of construction debris from the purported No Build Area. During the litigation, he had extensive discussions with Shiland and Kuplen regarding the terms of the No Build Zone and agreed to the sketch plan. In 1998, the lawsuit was settled with the then owners of all three lots (Shiland, Kuplen, and Pizzano) signing and delivering a Memorandum of Understanding on behalf of themselves, their heirs, successors in interest, and other interested parties that included an express acknowledgment of the existence of the No Build Area "as set forth on a Purchase and Sale Agreement dated June 16, 1994 by and between Shiland and Abram" and stating that "the conditions existing in the No Build Area are by mutual agreement." The copy of the sketch plan was attached to the Memorandum of Understanding when it was filed. Pizzano Aff. ¶¶ 3-4; Def. App., Exh. 3.

15. On May 1, 1998, a confirmatory deed from Abram, as Trustee, to Shiland was recorded with the registry at Book 14781, Page 445 (Shiland Confirmatory Deed). The Shiland Confirmatory Deed was intended to include certain rights and easements which were inadvertently omitted in the original deed. The description of Lot 1 in this deed contains the same language as the Kuplen Deed restricting the use of the No Build Area and making reference to the sketch plan of the No Build Area (Exhibit "A") supposedly recorded along with the Kuplen Deed. The sketch plan is not attached to the Shiland Confirmatory Deed. Pl. Facts, ¶ 10; Def. Facts, ¶ 10; Pl. App., Exh. G.

16. On March 19, 1999, the Shilands conveyed Lot 1 to the McLanes by a deed recorded with the registry at Book 15547, Page 437. The deed states that Lot 1 is subject to matters set forth in the Shiland Deed. It does not state that Lot 1 is subject to the Shiland Confirmatory Deed, which had included a reference to the Exhibit A sketch plan that was omitted in the original Shiland Deed. Pl. Facts, ¶ 11; Def. Facts, ¶ 11; Pl. App., Exh. H.

17. On June 1, 2000, Kuplen conveyed Lot 2 to the Gosselins by a deed recorded with the registry at Book 16375, Page 484 (Gosselin Deed). The description of Lot 2, the reference to the no build restriction and the Exhibit "A" sketch plan in the Gosselin Deed are the same as those in the Kuplen Deed, including that Lot 2 is subject to the Site Easement. Pl. Facts, ¶ 12; Def. Facts, ¶¶ 12, 14; Pl. App., Exh. I.

18. The Gosselins were represented by attorney Thomas P. Callaghan, Jr. (Callaghan) when they purchased Lot 2 from Kuplen. In their affidavit, the Gosselins attest that during the course of negotiations with the real estate broker, seller, and seller's attorney, no plan, sketch or indicia of any No Build Area was ever presented to them, and there were no oral representations concerning the dimensions of any No Build Area. The recorded Kuplen Deed for Lot 2 references the no build restriction and the sketch plan, and states that the property is subject to and with the benefit of the Site Easement. In addition, the owner's title insurance policy issued to the Gosselins in connection with their closing makes reference to a recorded Exhibit "A" containing all the easements and restrictions at issue. Opp. at p. 9; Def. App., Exhs. 1-2; Pl. App. K.

19. In April 2001, Raymond Gosselin initiated discussions with the McLanes and Pizzano regarding his interest in building a basketball court for his children in the No Build Area. A letter dated April 2, 2001, was sent from Raymond Gosselin to Robert McLane discussing the Gosselin's desire to build in the No Build Area. On April 4, 2001, the McLanes' lawyer, attorney E. James Kroesser (Kroesser), sent a fax of the sketch plan to the Gosselins' lawyer, Callaghan. The McLanes and Pizzano both refused to permit construction of a basketball court in the No Build Area. Pizzano Aff. ¶ 5; Def. App., Exh. 4.

20. On May 10, 2002, an affidavit executed by Attorney Kroesser under G.L. c. 183, § 5B, dated April 22, 2002, was recorded with the registry at Book 18690, Page 197 (Kroesser Affidavit). The Kroesser Affidavit states that Kroesser has "personal knowledge of the facts herein stated." Attached to the Kroesser Affidavit, as Exhibit A, is the sketch plan, which according to the affidavit was not recorded along with the Kuplen Deed due to mistake and/or inadvertence. The sketch plan, attached here as Exhibit B, is dated July 15, 1994. It depicts a "No Build Area" across Lots 1, 2, and 3. The southern boundary line of the No Build Area shows a course of N79'35'00"E and the length of two (out of three) segments as 121.63' and 89.86', for a total distance of 211.49'. There are no other distances or courses for any of the other boundaries. The eastern boundary is only depicted as running along a "Tree Line", the northern boundary is shown as running through an "Existing Wood Garage", and the western boundary appears to be aligned with existing landscaping just over the edge of Lot 1. The southeastern corner of the No Build Area appears to intersect with a rod. The sketch plan does not show any other monuments intersecting with the remaining bounds. Pl. Facts, ¶ 13; Def. Facts, ¶ 13; Pl. App., Exh. J; Def. App., Exh. 3.

21. In April 2011, the Gosselins prepared and circulated to the McLanes and Pizzano a document that intended to modify the terms and restrictions of the No Build Zone. Pizzano Aff. ¶ 5; Def. App., Exh. 5.

22. The Gosselins brought this action because they are in the process of trying to sell their home and believe that the presence of the Site Easement and the No Build Area as shown in sketch plan recorded with the Kroesser Affidavit are problematic to the marketability of their title. Pl. App., Exh. K.

23. During the summer of 2015, Laura E. Gillis and her husband Kevin Gillis made an offer to purchase the Gosselin Property. After discovering the restrictions upon use of the backyard, including prohibitions on building any structure without permission of the abutting lot owners, Gillis decided to execute a purchase and sale agreement conditioned upon the removal of the restrictions. Since the restrictions were not eliminated during the specified time frame, the purchase and sale agreement lapsed and they subsequently purchased a different property in the vicinity. Pl. App., Exh. L; Gosselin Aff. ¶¶ 3-4.

24. On January 14, 2016, real estate agent Lisa-Marie Cashman sent a letter to the Gosselins discussing how the restrictions have severely limited the number of prospective buyers and the asking price. Cashman informed the Gosselins that until such time as these restrictions are lifted, she saw no reasonable expectation that the Gosselin Property would be sold in the near future. Pl. App., Exh. M.

25. In February 2016, another real estate agent formerly of Coldwell Banker, Harry Fraser, sent the Gosselins a letter stating that the "restrictions are extremely problematic, in that each prospective buyer complained that such restrictions would substantially decrease the value of the subject property." In Fraser's opinion, the Gosselin Property was unlikely to be sold until the restrictions are eliminated. Pl. App., Exh. N.

Discussion

At issue in this case is whether two key provisions in the parties' chain of title, the Site Easement and the no build restriction, are valid and enforceable or are legally nullities. The Gosselins argue that the Site Easement is invalid since an owner may not impose a restriction on his own property that will be binding on subsequent purchasers. They also contend that the description of easements and restrictions in their deed, which do not correspond to any extant document in the chain of title, constitutes an indefinite reference pursuant to G.L. c. 184, § 25. The Defendants assert that the Site Easement, though not originally enforceable, became enforceable when Abrams, the grantor, later deeded Lots 2 and 3 out of common ownership. Additionally, the Defendants submit that G.L. c. 184, § 25, is not a remedy available to the Gosselins since, by its express terms, it does not apply to immediate parties to an instrument containing an indefinite reference or to parties on notice of any such indefinite reference, nor do property interests such as easements and restrictions created in a recorded instrument constitute an indefinite reference. Each argument is addressed in turn.

I. Site Easement

A party cannot have an easement in its own estate in fee. A valid appurtenant easement requires that there be a dominant and a servient estate. See Oldfield v. Smith, 304 Mass. 590 , 593 (1939). "So long as there was a common ownership of the two parcels there could be no easement in favor of one lot operating as a burden on the other." Goldstein v. Beal, 317 Mass. 750 , 754 (1945), citing Johnson v. Jordan, 2 Met. 234 , 239 (1841); Mt. Holyoke Realty Corp. v. Holyoke Realty Corp., 284 Mass. 100 , 105 (1933). "If any easement came into existence it was only upon a severance of the common ownership." Garrity v. Snyder, 345 Mass. 121 , 124 (1962), quoting Goldstein, 317 Mass. at 754.

On August 31, 1994, Abram, as Trustee, recorded the Site Easement with the registry at Book 12727, Page 161, which purportedly set forth an easement for the benefit of Lots 2 and 3. The language of the easement is unambiguous. It prohibits buildings, structures, and the like from being located within ten feet from the boundary lines of Lots 2 and 3 along Essex Street. It was apparently intended to retain proper visibility from the properties to and along Essex Street so that entry and exit from these lots onto Essex Street would be safer. Pizzano Aff. ¶ 6. The easement also reserved to the grantor the right to enter the lots to remove trees and regrade within the ten foot wide easement. Pl. Facts, ¶ 7; Def. Facts, ¶ 7; Pl. App., Exh. D. At the time when the Site Easement was created, Abrams owned both Lots 2 and 3. Thus, the Gosselins are correct that at the time of its creation, Abrams could not impose the easement on himself as common owner of the lots.

This does not, however, mean that the Site Easement as stated in the Gosselin Deed is invalid. On September 1, 1994, Abram, as Trustee, conveyed Lot 2 to Kuplen by the Kuplen Deed. The property description in the Kuplen Deed provides that Lot 2 is "[s]ubject to and with the benefit of a site easement recorded on August 31, 1994 as Instrument No. 366, Book 12727, Page 161." Pl. Facts, ¶ 8; Def. Facts, ¶¶ 8, 15; Pl. App., Exh. E. On April 14, 1995, Abram, as Trustee, conveyed Lot 3 to Pizzano by the Pizzano Deed. As with the Kuplen Deed, the description of Lot 3 in the Pizzano Deed also referenced the Site Easement. Pl. Facts, ¶ 9; Def. Facts, ¶¶ 9, 16; Pl. App., Exh. F. By expressly referring to and incorporating the Site Easement, both the Kuplen and Pizzano Deeds reserved and granted the Site Easement, and it became enforceable upon Abrams' conveyance of Lot 2 and Lot 3 to Kuplen and Pizzano, respectively. It was at this point that common ownership of the properties was severed and the conveyances were explicitly subject to and benefited by the Site Easement. The Gosselins' chain of title, including the Kuplen Deed, specifically subjects the Gosselin Property to the Site Easement for the benefit of the other properties. The Site Easement remains enforceable against them.

II. Indefinite Reference

The Gosselins also argue that the no build restriction is also a nullity under G.L. c. 184, § 25, the indefinite reference statute. Section 25 provides:

No indefinite reference in a recorded instrument shall subject any person not an immediate party thereto to any interest in real estate legal or equitable, nor put any such person on inquiry with respect to such interest, nor be a cloud on or otherwise adversely affect the title of any such person acquiring the real estate under such recorded instrument if he is not otherwise subject to it or on notice of it. An indefinite reference means (1) recital indicating directly or by implication that real estate may be subject to restrictions, easements, mortgages encumbrances or other interests not created by instruments recorded in due course, . . . and (4) any other reference to any interest in real estate, unless the instrument containing the reference either creates the interest referred to or specifies a recorded instrument by which the interest is created and the place in the public records where such instrument is recorded.

Id. (emphasis added). In other words, the statute provides that a transferee who is "not an immediate party thereto" is not bound by an "indefinite reference in a recorded instrument" unless the transferee has notice of the encumbrance or the instrument containing the reference that creates the interests or supplies the record reference to the creation of the interest. Id.

In seeking to invoke § 25, the Gosselins first suffer from being "an immediate party thereto." The Gosselins are a party to the Gosselin Deed, where the reference to the sketch plan and no build restriction that they are here contesting appear. Asian Am. Civic Ass'n v. Chinese Consol. Benev. Ass'n of New England, Inc., 43 Mass. App. Ct. 145 , 14950 (1997) (party to the recorded instrument not eligible to raise defense based on G.L. c. 184, § 25); see Eno & Hovey, Mass. Prac. Real Estate Law c. 28 § 2.16 (4th ed. 1995). Further, it is likely that the Gosselins had notice of the restriction. The deed conveying the Gosselin Property contained the same description of the no build restriction and reference to the No Build Area sketch plan as in the Kuplen Deed and the deeds to Pizzano and the Flemings. Though the Gosselins attest that during the course of negotiations for their purchase of Lot 2, no plan, sketch or indicia of any No Build Area was ever presented to them, and there were no oral representations concerning the dimensions of any No Build Area, they did not attest that they were unaware of the disputed easements and restrictions in their chain of title. Rather, they only contest their knowledge as to the scope of these property rights. The owner's title insurance policy issued to the Gosselins in connection with their closing also makes reference to a recorded Exhibit "A" containing the restrictions at issue. Pl. Facts, ¶ 12; Def. Facts, ¶¶ 12-13; Opp. at p. 9; Def. App., Exhs. 1-2; Pl. App. I, K.

Even if the Gosselins are entitled to invoke § 25, their contention that the sketch plan constitutes an indefinite reference because it was not recorded at the time of their deed's recordation is also flawed. General Laws c. 184, § 25, provides: "No instrument shall be deemed recorded in due course unless so recorded . . . as to be indexed in the grantor index under the name of the owner of record of the real estate affected at the time of the recording." See Asian Am. Civic Ass'n, 43 Mass. App. Ct. at 149; Devine v. Town of Nantucket, 449 Mass. 499 , 507- 508 (2007). The sketch plan, although dated July 15, 1994, and seemingly prepared in association with the Kuplen Deed that first created the no build restriction, was not recorded until May 10, 2002, after the Gosselins were conveyed their property by the Gosselin Deed in 2000. While the sketch plan was recorded late, references were made in the chain of title to Lots 1, 2, and 3 to an Exhibit "A" sketch plan recorded at Book 12731, Page 25 of the registry, the same book and page as the Kuplen Deed recording.

The sketch plan was finally recorded under G.L. c. 183, § 5B. Section 5B provides:

Subject to section 15 of chapter 183, an affidavit made by a person claiming to have personal knowledge of the facts therein stated and containing a certificate by an attorney at law that the facts stated in the affidavit are relevant to the title to certain land and will be of benefit and assistance in clarifying the chain of title may be filed for record and shall be recorded in the registry of deeds where the land or any part thereof lies.

Id. (emphasis added). Therefore, "§ 5B, by its terms, appears to contemplate that an attorney's affidavit prepared and recorded in accordance with the requirements of that statute, by 'clarifying' the chain of title, will necessarily alter at least in some respect that chain of title as it is reflected in the documents previously recorded." Bank of Am., N.A. v. Casey, 474 Mass. 556 , 563 (2016). "The Legislature's choice of the word 'clarifying' suggests that the attorney's affidavit must be limited to facts that explain what actually occurred, and are not inconsistent with the substantive facts contained in the original document." Id. at 565-566, citing Allen v. Allen, 86 Mass. App. Ct. 295 , 299-300 (2014) (facially proper acknowledgment, reflecting grantor signed deed in presence of notary, deemed invalid where evidence established grantor in fact did not execute deed in notary's presence on date stated in deed); see Pinti v. Emigrant Mtge. Co., 472 Mass. 226 , 244 (2015) (mortgage holder may record attorney's affidavit to demonstrate compliance with notice provisions); Eaton v. Fed. Nat'l Mtge. Ass'n, 462 Mass. 569 , 589 n.28 (2012) (mortgage holder may use attorney's affidavit to establish it held note or was agent of note holder at time of foreclosure sale). "These decisions serve to illustrate the point we make here, which is that § 5B permits attorney's affidavits to explain a set of existing facts relevant to the chain of title where the facts had not been stated explicitly in the property record, whether through inadvertent omission or mistake or because no document previously called for them." Casey, 474 Mass. at 566 n.19.

Here, the undisputed facts indicate that the Kroesser Affidavit was a § 5B attorney's affidavit sufficient to correct or cure the defect in the Kuplen Deed and, in turn, the Gosselin Deed. The defect was the omission of the sketch plan showing the No Build Area which was supposed to be recorded with the Kuplen Deed. The Kroesser Affidavit supplied the missing sketch plan, referenced the book and page numbers of the previously recorded deeds where the sketch plan was intended to be recorded, and confirmed that the sketch plan had not been recorded at the time of the Kuplen Deed because of mistake and/or inadvertence. The Kroesser Affidavit connected the sketch plan to the prior deeds, thereby clarifying the chain of title. The Kroesser Affidavit also attests that Kroesser has "personal knowledge of the facts herein stated." The Gosselins do not challenge Kroesser's personal knowledge on this subject. The Kroesser Affidavit, filed and recorded pursuant to § 5B, supplied the missing sketch plan, explained the circumstances of the omission, and confirmed that Kroesser had personal knowledge of the facts. It operated to cure the original defect in the recording of the Kuplen Deed. The Kuplen Deed, and subsequent deeds omitting the sketch plan, are deemed remedied through the curative effect of the Kroesser Affidavit. Id. at 568.

The Gosselins argue that even if the sketch plan is deemed recorded through the § 5B affidavit, the language in their deed and the sketch plan still do not provide a sufficient property description of the restriction and location of the No Build Area because there are no dimensions in the deed or on the plan that can be used to ascertain the location of the No Build Area. In addition, they assert that the covenant concerning "no dwelling, structure or improvement" be constructed within the No Build Area shown as field, refers not to the unrecorded sketch plan, but the 1994 Plan, which does not depict a No Build Area.

"[R]estrictions on land are disfavored, and they 'in general are to be construed against the grantor.'" Stop & Shop Supermarket Co. v. Urstadt Biddle Props., Inc., 433 Mass. 285 , 290 (2001), quoting Ward v. Prudential Ins. Co., 299 Mass. 559 , 565 (1938); Brown v. Linnell, 359 Mass. 446 , 447 (1971). Nonetheless, they must be construed "with a view to avoiding results which are absurd, or inconsistent with what was meant by the parties to or the framers of the instrument." Maddalena v. Brand, 7 Mass. App. Ct. 466 , 469 (1979), quoting Chase v. Walker, 167 Mass. 293 , 297 (1897). A restriction, like a deed, "is to be construed so as to give effect to the intent of the parties as manifested by the words used, interpreted in the light of the material circumstances and pertinent facts known to them at the time it was executed." Walker v. Sanderson, 348 Mass. 409 , 412 (1965), quoting Bessey v. Ollman, 242 Mass. 89 , 91 (1922); Patterson v. Paul, 448 Mass. 658 , 665 (2007); Sheftel v. Lebel, 44 Mass. App. Ct. 175 , 179 (1998). The restriction "must be construed beneficially, according to the apparent purpose of protection or advantage . . . it was intended to secure or promote." Maddalena, 7 Mass. App. Ct. at 469, quoting Jeffries v. Jeffries, 117 Mass. 184 , 189 (1875); Chatham Conservation Foundation, Inc. v. Farber, 56 Mass. App. Ct. 584 , 590 (2002). "While the words of the deed remain the most important evidence of intention, they must be construed in light of the attendant circumstances to interpret an ambiguous meaning." Melone v. Town of Lancaster, 24 LCR 354 , 359 (2016), citing Hamouda v. Harris, 66 Mass. App. Ct. 22 , 25 (2006). Any ambiguity in a restrictive covenant must "be resolved in favor of the freedom of land from servitude," meaning the less restricted use, while still respecting the purposes for which the restriction was established. Well-Built Homes, Inc. v. Shuster, 64 Mass. App. Ct. 619 , 629 (2005); McDonald's Corp. v. Rappaport, 532 F.Supp.2d 264, 274 (D. Mass. 2008).

The deed to the Gosselins refers to the No Build Area twice. It first states that the premises are subject to and with the benefit of "right and easement to use those portions of Lots 2 and 3 located within the 'No Build Area' shown on a certain sketch plan . . . for passive recreational and uses, included, but not limited to, gardening and landscaping purposes, and for such other uses as may be mutually agreed by the present and/or future owners of Lots 1, 2, and 3." The sketch plan depicts a "No Build Area" across Lots 1, 2, and 3. The southern boundary line of the No Build Area shows a course of N79'35'00"E and the length of two (out of three) segments as 121.63' and 89.86', for a total distance of 211.49'. There are no other distances or courses for any of the other boundaries. The eastern boundary is only depicted as running along a "Tree Line", the northern boundary is shown as running through an "Existing Wood Garage", and the western boundary appears to be aligned with existing landscaping just over the edge of Lot 1, adjacent to an "Existing Pool". The southeastern corner of the No Build Area appears to intersect with a rod. The sketch plan does not show any other monuments intersecting with the remaining bounds. Pl. App., Exh. J. The No Build Area is referenced a second time in the subsequent paragraph, where it states that the Gosselins "covenant and agree that no dwelling, structure, or improvement of any kind or nature shall ever be located, constructed, placed or allowed to stand within the open space, No Build Area, presently shown as a field."

The sketch plan is difficult to interpret given the lack of dimensions and monuments referenced. Moreover, the sketch plan contains writing that states it is approximate and "not to scale." Neither the 1994 Plan nor the sketch plan depict a field or open space area as referenced in the various deeds to Lots 1, 2, and 3. Even if it did, using such indefinite bounds to ascertain the location of the No Build Area would be impossible without more information, especially given that the location of the field or open space area may have changed over the last two decades. The scope of the restriction is clearly ambiguous. The facts before the court do not adequately detail attendant circumstances that could reveal evidence of intention and aid in the interpretation. Where evidence as to the scope and location of an encumbrance is conflicting and indistinct, it is a question of fact for the judge to decide what was intended. See Town of Bedford

v. Cerasuolo, 62 Mass. App. Ct. 73 , 80 (2004) ("Where the evidence is conflicting, it is a question of fact for the judge to decide what location was intended."); Adler v. Town of Chilmark, No. 04-P-1328, 2005 WL 1903297, at * 3 (Aug. 10, 2005); Fred F. Cain Inc. v. 580 Main St. Wilmington MA PR356 LLC, 21 LCR 185 , 188 (2013). The extent of the restriction cannot be resolved in light of the absence of information in the record concerning the location of the No Build Area and the intent of the original grantor in establishing the restriction.

Likewise, even if the restriction against building in the No Build Area is found to be applicable to the Gosselin Property, the court must then consider whether the restrictive covenant is enforceable. It will be incumbent upon the court to determine if the restriction in question is "of actual and substantial benefit to a person claiming rights of enforcement." G.L. c. 184, § 30. Even if the court finds such a benefit, it must still determine if any of the five statutory exceptions are applicable. See Connaughton v. Payne, 56 Mass. App. Ct. 652 , 655656 (2002). The five exceptions are:

(1) changes in the character of the properties affected or their neighborhood, in available construction materials or techniques, in access, services or facilities, in applicable public controls of land use or construction, or in any other conditions or circumstances, reduce materially the need for the restriction or the likelihood of the restriction accomplishing its original purposes or render it obsolete or inequitable to enforce except by award of money damages, or

(2) conduct of persons from time to time entitled to enforce the restriction has rendered it inequitable to enforce except by award of money damages, or

(3) in case of a common scheme the land of the person claiming rights of enforcement is for any reason no longer subject to the restriction or the parcel against which rights of enforcement are claimed is not in a group of parcels still subject to the restriction and appropriate for accomplishment of its purposes, or

(4) continuation of the restriction on the parcel against which enforcement is claimed or on parcels remaining in a common scheme with it or subject to like restrictions would impede reasonable use of land for purposes for which it is most suitable, and would tend to impair the growth of the neighborhood or municipality in a manner inconsistent with the public interest or to contribute to deterioration of properties or to result in decadent or substandard areas or blighted open areas, or

(5) enforcement, except by award of money damages, is for any other reason inequitable or not in the public interest.

G.L. c. 184, § 30. As the record now sits, exception (3) does not apply, as this restriction is not part of a common scheme. See G.L. c. 184, § 27(b)(1) (common scheme involves at least four or more contiguous parcels). There is insufficient evidence to ascertain whether the restriction is of substantial benefit to the Defendants and if any of the four remaining exceptions in § 30 applies so as to make enforcement inequitable as against the Gosselins. Since genuine issues of material fact exist as to the scope and enforceability of the no build restriction, summary judgment on the no build restriction cannot be entered.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, Plaintiffs' Motion for Summary Judgment is DENIED. Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment is ALLOWED IN PART. It is DECLARED that the Site Easement as it appears in the Kuplen and Gosselin Deeds is valid and enforceable. The remainder of Defendants' Motion for Summary Judgment is DENIED. A telephone status conference is set down for January 20, 2017 at 10:30 am.

SO ORDERED

RAYMOND J. GOSSELIN and LINDA E. GOSSELIN v. RUDOLPH PIZZANO, ROBERT M. McCLANE, JR., GRATIA L. McCLANE, GARWIN K. FLEMING, JR., and PAGE H. FLEMING.

RAYMOND J. GOSSELIN and LINDA E. GOSSELIN v. RUDOLPH PIZZANO, ROBERT M. McCLANE, JR., GRATIA L. McCLANE, GARWIN K. FLEMING, JR., and PAGE H. FLEMING.